Even if we had low-emissions, low-noise, low-accident cars, there’d still be the concrete jungle surface needed to drive them - and loads of emissions to make the steel and cement of highways.

Although cars carrying four or more people directly to a medium-distance destination can be relatively efficient per pers-km, people buy oversized cars imagining some dream holiday, then use them for daily life on one-person trips that (electric-) bicycles and/or trains could do - car-sharing could help avoid that and solve the EV-range issue (although personally, my dream holidays would be in places with no cars at all).*in the USA I bet this is pretty different in countries that have kept up with switching the grid to renewables.

Even still, each battery pack and the 6,000lb car put more strain on the mines, factories, and roads. Those resources could be used for stuff like ebikes where you only need a fraction of the power to get the bike to move forward.

EVs have their place, but eventually we are going to have to reckon with a post-car reality. Building trans, trams, BRTs (fast bus lines) and bike lanes will make cities faster to get around, without having to own a vehicle to get groceries a mile down the road. Making sidewalks comfortable and wider will also make stuff feel less shitty.

We’ll probably get to a point where you can rent a vehicle if you really need it for remote areas, but day to day, you can pocket that insurance/maintenance/fuel/depreciation money and use it on something else.

6000lb car

Absolutely clueless American take on the average size of a car 😂

EVs are heavy. While they vary by make and model, the sedans like Lucids around Vancouver BC and WA weigh 5,200lbs without any cargo, bike racks, ski racks, or people in it.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucid_Air

Sedans to SUVs also weigh in the 3,500-5,200 lbs when empty. https://electrek.co/2021/08/02/how-much-does-a-tesla-weigh-comparing-each-model/

Electric trucks (not pickups) are also getting more popular, and will also need to be factored into things like updated crash barriers, bridges, offramps and older city roads built on top of thin concrete structures from the 1900s. It’s going to cost cities a lot of money if we don’t emphasize a reduction in cars and trucks going forward. We should be pushing rail and bikes harder.

WRONG!! Velomobiles and other man-powered (or nature powered) land vehicles absolutely exist.

I’d argue if you’re making the human more efficient than walking, you’re reducing CO2 output compared to simply walking there.

If a reduction in human CO2 compared to distance traveled isn’t good for the environment, then nothing is good for the environment.

Do those really count as cars in the usual sense of the term?

Does it have to be usual when the qualifier on the negative is “none”?

I’m not sure I follow.

They are saying there are zero cars that fit the bill. Why is an “unusual” car not part of “all cars”? It’s a basic question of what set is being considered.

Of course if you limit “cars” to be anything that is over 1000lbs with an engine, THAT set of “cars” is going to be far less economical than some other vehicles that many would still call a “car”.

I personally think of “automobiles” so self powered vehicles. Velomobiles (human powered) are cool but i live in the mountains and I do not get decent comfort with them.

My daily driver, is a Renault Twizy. It comes with a (electric) engine, steering wheel, gas and brake pedals, a roof, a windshield and other stuff most people associate with “car”. It also weights about 400 kg empty and four of them use less parking space than one traditional car. I power it with solar power for my own roof. It maxes out at about 80 km/h which makes it suitable for short trips on the Autobahn.

Might not be a usual car but still quite traditional and much more energy efficient than a 2100 kg Tesla.

I get you now. But I still feel like “car” is intended to be (or ought to be) narrowly defined as a 1000-lb metal box on wheels with an engine. I think referring to other vehicles as “cars” just muddles the discourse.

Then again, I’m conflicted. If I replace “car” with another word like “meat” or “milk”, I have a different reaction. If someone wrote an article about factory-farm chickens vs free-range chickens and said, “There really is no such thing as ‘good’ meat,” I’d definitely chime in with, “What about vegan meat?”

Maybe it’s because I perceive the gap between animal meat and vegan meat as narrower than the gap between 1000-lb metal boxes with engines and other types of vehicles. Like… if I have to pedal, it’s not a car.

Is the Flintstones car a “car”?

Well, in that vein, there are many light weight solar powered “cars”. Some formula of solar panels don’t use much of rare/bad materials, and salt batteries are already a thing, so certain constructions wouldn’t need to climb much of a hill to become a net-positive.

Overall a good summation of most of the facts, however, they did gloss over an important issue with EVs and the grid.

Yes, the grid can handle the additional load with proper development, but adding any new load to the grid at this point will necessarily slow our transition away from fossil electricity, unless you somehow charge only during times of excess renewable energy. Currently, this is not possible.

Also, I think there’s lots of other useful things we might find to do with cheap excess energy that will be available at certain times. I don’t know exactly what but pumping or desalinating water is one possible idea. Sort of an inverse peaker plant—a cheap piece of infrastructure that may sit idle for a time but kicks on when there is more energy than we can use to do some practical work.

unless you somehow charge only during times of excess renewable energy. Currently, this is not possible.

This is possible in many European nations, who publish live data on renewal percentage.

In the Netherlands, I have the live green energy data in home assistant. This could quite easily be used to turn on and off car charging

Tibber even does it super easily for normies — you connect your EV account to it and it takes control of the charging rate such that your car is ready to go the next morning, but charges it during the cheapest periods (which generally are the greenest ones, when there’s a sudden influx of solar or wind). AFAIK this even works if you’re not on a dynamic pricing contract, you just obviously wouldn’t get the price benefit.

Personally, I also got Home Assistant set up to remote start my large appliances in exactly the best moment to make use of the most green energy. Probably doesn’t make a massive impact, but it doesn’t cost me much either.

Is it practical for vehicle charging though? From what I’ve seen, typically these periods of abundant green energy are only for short periods of the day or year. At other times, additional energy will be generated by gas or other dirty source.

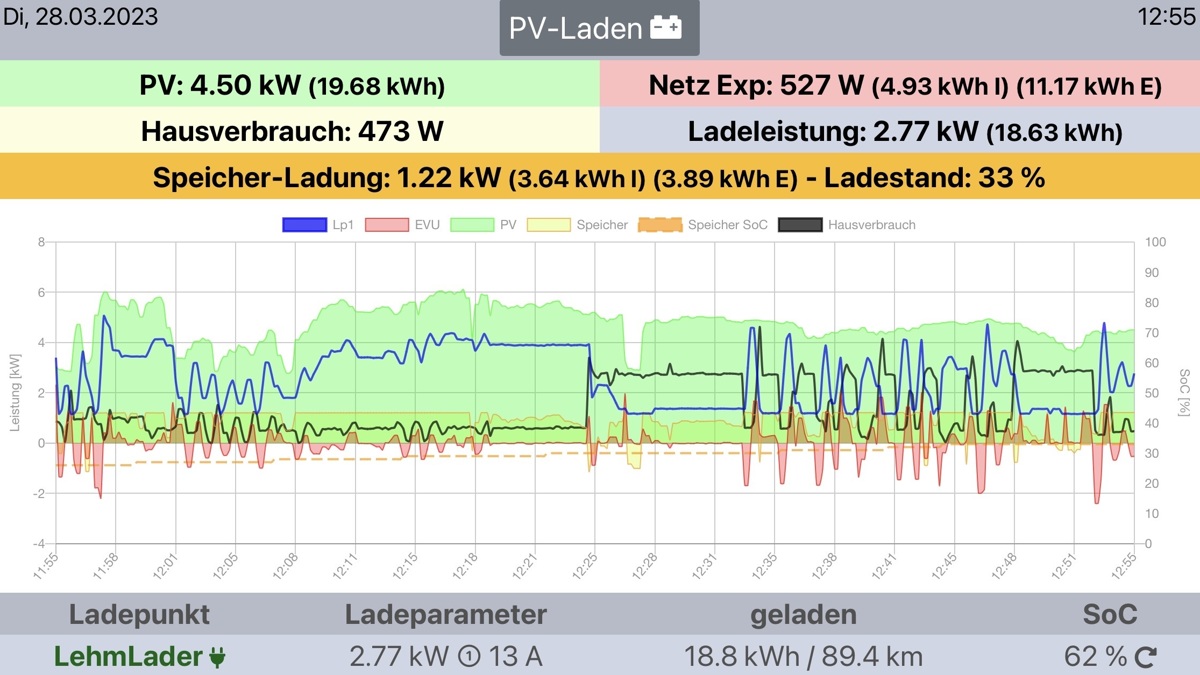

This is very possible and practical, in fact I have been doing it for a few years with OpenWB and my own 10.5 kWp PV generator.

This is based on a current sensor where the mains enter my house. OpenWB tries to increase or decrease the EV charging current so no current is coming into the house or going out of the house. So when I switch on the coffee machine, within a second or so OpenWB will decease the current to the car so I don’t have to buy energy.

In that image you can see that until 12:08 we have intermittent sun / pv production (green line) and most of the time very erratic power usage in the house (black line). The system is wildly adjusting the car charging speed (blue line) to keep me from buying or selling electrical power (red line).

Once set up this works really well and I rarely use non-PV power to charge my car - even in deepest winter I guess 50 % of car charging is done by solar.

Here in Germany people now start getting dynamic pricing where the cost of electricity changes every 15 minutes - mostly it’s cheap when the wind blows and the sun shines. Wallboxes like OpenWB can use that pricing to decide when to charge your car. Others use just Solar radiation to automatically decide when to charge. This is all technology available out of the box right now.

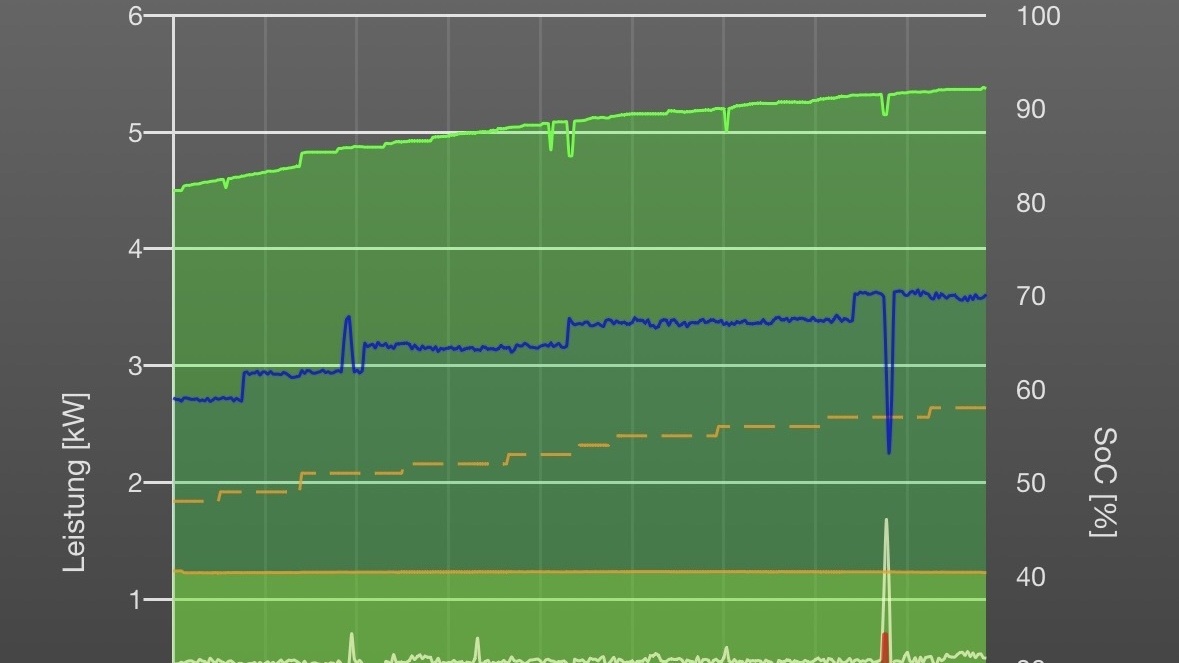

Some more screenshots:

Green is solar production steadily increasing during the morning.

Orange is the constant charging of the house Battery. We have a 10 kWh Battery but carge only op to 70% to incerase it’s lifetime.

Yellow is the house consumption. No idea what the spike at 8:45 is.

Blue is te EV charging power constantly increasing as the PV power goes up.

Compare this to the the more turbulent situation at 9:00h:

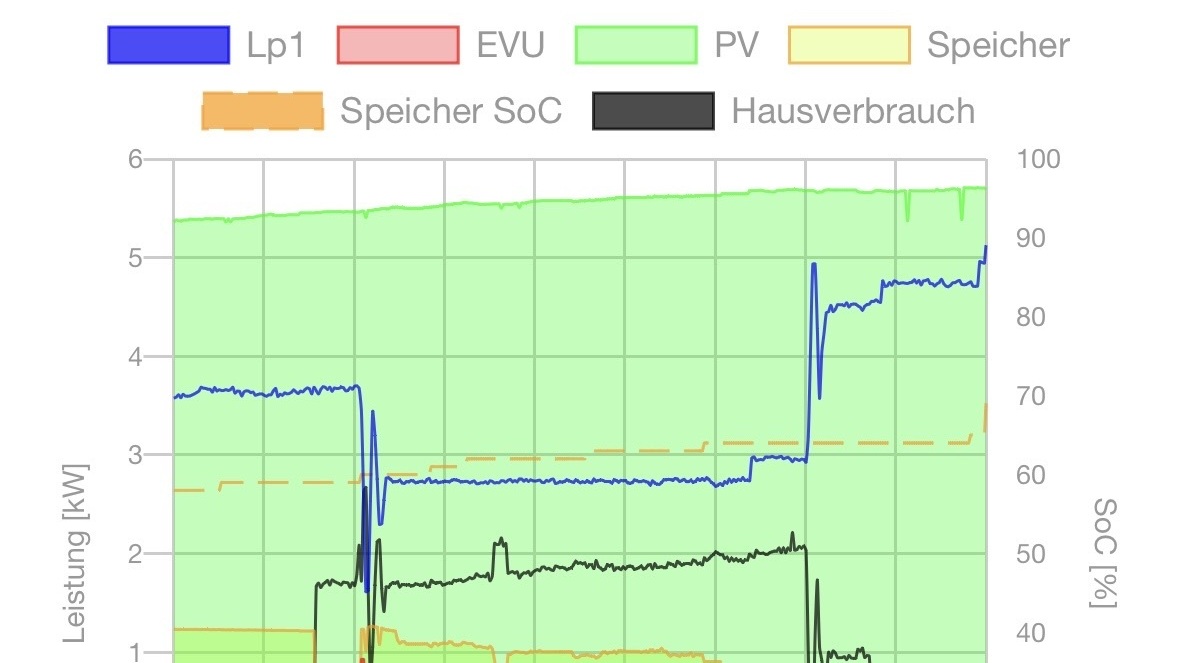

I take a shower and the hearpump kicks in to replace warm water in the storage tank thus the house consumption (here black not yellow) inceraseses.

At first this means charging of the house battery (orange) drops to nearly zero.

At 9:05 reduction of EV charging kicks in to give the house battery priority.

At 9:30 you se hoys battery charging go sliwer because we nearly reached it’s maximum charge.

At 9:40 heat pump is done but I make a coffee. Then at 9:40 nearly all power is used for EV charging.

all this works completely automated intense of. These are commercially available easy products. Only the nerds look inside what’s actually happening.

This example is driven by my own PV, but it is trivial to drive it by power prices or country wide power production.

Unfortunately the images seem to be cropped in a strange way - let’s try again:

That was super cool to read about, cheers for sharing your set up!

That’s according to a peer-reviewed study funded by the Ford Motor Company, a company that makes most of its profits from gas-powered vehicles.

If you want to see if a tech is part of a renewable future, it is direct emissions that should be counted. EVs are at zero. They don’t emit CO2 when running, when being produced or when being disposed of. They use electricity and transport, two things that we can provide without emitting CO2. They are a piece of the puzzle of a sustainable society, something thermal cars will never be, and something these graphs hide.

Of course we will be better off without cars and trucks, but the road towards them being totally gone is long, and it is time we don’t have.